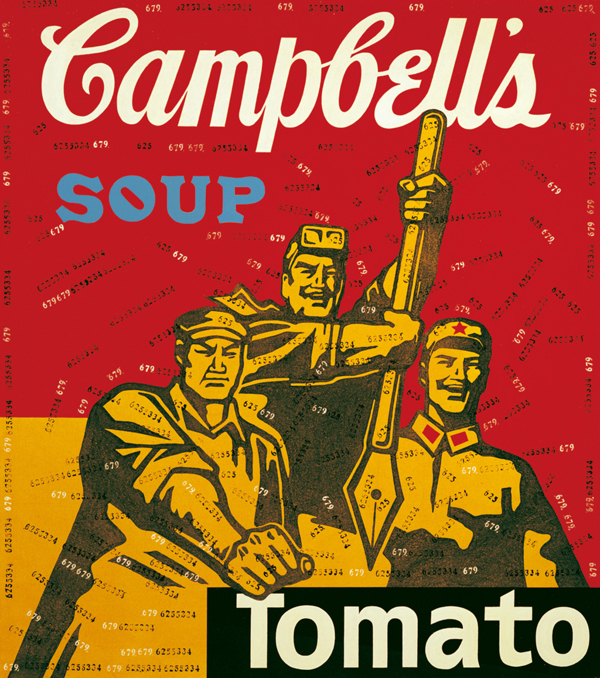

Lot 127

Great Criticism Series-Campbell's Soup

WANG Guangyi (Chinese, 1957)

2000

Oil on canvas

200 x 175 cm

Estimate

TWD 12,300,000-18,450,000

HKD 3,000,000-4,500,000

USD 384,600-576,900

Sold Price

TWD 7,695,652

HKD 1,770,000

USD 228,387

Signature

+ OVERVIEW

Wang paints in the style of Political Pop, an art movement that began in the early 1990s. Political Pop utilizes images and icons of the Cultural Revolution in an ironic or questioning way. With the opening of China in 1977 after 10 years of the Cultural Revolution, the contemporary art scene exploded. Many artists adopted avant-garde styles to express their modern concerns and individuality. However, the authorities were reluctant to accept art which emphasized the individuality of the artist and posed questions about contemporary life. During the 1980s, a tremendous energy ran through the art scene, and artists associated themselves with the democracy movement. All this changed in 1989 when the authorities allowed the first official avant-garde exhibition at the National Museum in Beijing. At the opening of the show, shots were fired by an installation artist; the exhibition was immediately closed down.

The art scene was devastated by this event and spent the next few months trying to figure out what direction they should take. Then in June 1989, Tiananmen Square erupted. The whole of society became quiet for the next couple of years. A realization seemed to dawn on the art world, too much open questioning or criticism would unleash uncontrollable powers. In the early 1990s, contemporary art began to reappear.Gone was the open anger, anguish and searching of the pre-1989 works, instead in a very Chinese way they had been replaced by irony and humor. Political Pop, of which Wang is one of the most renowned practitioners, chose the voice of irony while the other great movement Cynical Realism followed the voice of humor. This playfulness, in many ways, is even more subversive to the Oriental mind, but the authorities could hardly object to the use of its most revered icons.

In his "Great Criticism Series", Wang combines iconic images from the Socialist Art posters of the Cultural Revolution with iconic images of Western Consumerism. Strong, stoic and idealistic figures of Maoism, soldiers, laborers and farmers are juxtaposed with equally strong and powerful logos of Western consumerism often with the word 'NO' clearly imposed on the canvas. On first view, it seems incongruous to place images of revolutionary zeal with images of almighty consumerism. But what Wang has created are images that are emblematic of China's contemporary struggle, grappling with its past while figuring out its future. Wang seems to be suggesting that both sets of symbols are dangerous. But this is a superficial reading. For many Chinese, Wang included, the Cultural Revolution is not a black and white issue as it would be for most Westerners. Many Chinese look back at that time with a certain nostalgia notwithstanding the horrors that took place, it was an easy time for many, no work and no school. In a very Chinese way, most things are imbued with contradictions, contradictions we can live with. Wang has also said he drinks Coca-cola everyday, but it's one of his most common images. Is he really criticizing or is he provoking us to ask questions? His works are truly emblematic.

On the surface, Wang's style may seem to be an appropriation of the pop art of Warhol and Lichtenstein, incorporating everyday images in a flat pop art style. But his work at the beginning of the 1990s was just as revolutionary in China as theirs was in 1960s America. Traditional Chinese art was very conservative and tradition bound. Great art was produced by copying the great masters. The very act of using a foreign style of painting was in itself reactionary and daring. What separates Wang's art from that of the Western pop-artists is the unique and complex imagery he uses, which has a very Chinese foundation. The form looks similar, but the meaning is very different.

"Great Criticism Series-Campbell's Soup" has three powerful, stoic figures of the Cultural Revolution, a soldier, a laborer and a miner seemingly lifted directly from a Mao era revolutionary poster which were ubiquitous all over China. They are defiantly looking out toward the future, but a future of what? Western Consumerism? The laborer is making a strong, defiant gesture with his right arm and fist as if saying 'No'. The soldier and miner seem to be smiling at the vision of the future, a world filled with Campbell's Tomato soup. And this is the great dichotomy of Wang's works, should we welcome the new consumerism or reject it outright. No easy answers are given, just as no easy answers exist for the right and wrongs of the past. The miner is holding a large pen, which often replaces the guns of the original revolutionary posters. Once again the meaning is enigmatic. Is Wang suggesting the power of the pen is stronger than the power of force? Is an artist using a pen, able to bring us to the truth?

In "Great Criticism Series - Campbell's Soup" the common 'NO' of the "Great Criticism Series" is replaced with 'Tomato', the flavor of the soup. Of course 'Tomato' has immediate sound resonances with the word 'No', and may be a play with words, which brings a knowing smile to the viewer. Significantly, the laborer's fist comes down on the first letter of Tomato. Tomatoes are a fruit for Chinese people and they would have no concept of 'tomato soup'. A further infiltration of Western culture that should be guarded against?

All of the 'The Great Criticism Series" is covered in stenciled repeated numbers. In 'The Great Leap Forward' of the 1950s Mao considered replacing personal names in China with numbers. The scheme was carried out on an experimental basis in a number of areas. Each laborer had a number stitched on their back, perhaps the ultimate depersonalization of everyone. Equally, consumerist societies are obsessed with numbers, the numbers on the price tag, the amount in bank accounts. Once again, Wang is enigmatically posing a very deep question: do we accept being classified as numbers?

Wang Guangyi was the leading light of the emergence of new contemporary art in the 1990s. He led the movement that appropriated Western styles, which were then molded to reflect the questions, concerns and experiences of young Chinese artists. His "Great Criticism Series" remains the defining image of a whole new era of expression in modern, post-Cultural Revolution China.

Modern & Contemporary Asian Art

Ravenel Autumn Auction 2008 Hong Kong

Monday, December 1, 2008, 12:00am