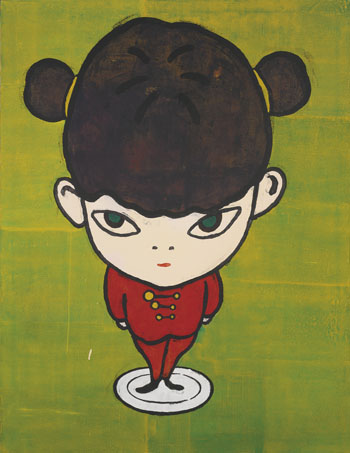

Lot 509

Chinese Girl on the Dish

Yoshitomo NARA (Japanese, 1959)

1993

Acrylic on canvas

130 x 100 cm

Estimate

TWD 13,680,000-15,960,000

HKD 3,600,000-4,200,000

USD 461,500-538,500

Sold Price

TWD 16,000,000

HKD 4,320,000

USD 557,419

Signature

Acquired directly from the artist by Galerie Tokyo Humanité, Tokyo, Japan

Private Collection, Asia

EXHIBITED:

Be Happy, Galerie Tokyo Humanité, Tokyo, Japan, November 29 - December 18, 1993

ILLUSTRATED:

Yoshitomo Nara: The Complete Works, Chronicle Books LLC, San Francisco, 2011, color illustrated, p. 86

+ OVERVIEW

The diversity of Yoshitomo Nara’s followers is an achievement seldom reached by a living artist. With a strong sub-culture cult following across the globe, combined with fine art pieces realizing prices of over one million US dollars, Nara’s meteoric rise to prominence within the past decade comes as no surprise. With this growth in status comes growth in value; Nara’s works have more than doubled in investment worth since 2004, and continue to thrive in a demanding world market.

Nara began his rapid ascension within the art world in the 1990s, and is often closely associated with Japanese artistic movements of that period. His work is commonly attributed as belonging to Takashi Murakami’s “Superflat,” an artistic theory which draws clear inspiration from Japanese manga and anime, with ties and forays into otaku pop-culture fanatic obsession. However, while Nara’s works share characteristics of Superflat in the use of simple lines and lack of visual dimension, the subject matter vastly differs from that of most Superflat artists. Murakami developed the theory as a mocking critique for consumerism and cultural objectification within the society around him, and often employs the sexualization reminiscent of fetishist Lolita culture, along with playful and childish imagery. In such subject matter, Nara takes a distinct departure from the movement. His works do not focus on a consumerist culture, and the children he depicts are neither sexual nor childish. Indeed, Nara himself rejects the clichéd association of his work with Superflat, distancing himself by stating: “the entire 1990s, the entire decade, I was not even in Japan. I was absent. It’s a mystery to me why I’m so often associated with a movement that is so specific to that time and to that place.”

While rejecting affiliation with Superflat, Nara openly acknowledges the influence on his artwork from another genre of artistic expression— children’s picture books. Within such a seemingly innocent medium, Nara recognized the potential for greater visual impact, asserting that “in a picture book you have a single image that can contain an entire narrative.” While deceptively simple in form, Nara emulates this theory of a condensed, yet fully formed story conveyed through a solitary impression.

Throughout his works, Nara utilizes the depiction of children as a conduit for the expression of his ideals. Nara’s children form the perfect amalgam, imbued with the subtle ire and rebellious nature of Nara’s thematic approach, while maintaining the outward innocence of his stylistic inspiration. With their comically oversized heads placed upon petite and fragile frames, Nara’s children stare out at the world around them through enormous eyes narrowed in suspicion and distrust. Often armed with miniature knives, or with glowingly lit cigarettes dangling dangerously from their fingers or lips, these children stand defensively alone against the menacing expanse of nothingness surrounding them. Nara plays on the collective perception of innate innocence in children. Speaking in reference to his own childhood, he states simply, “when you are a kid, you are too young to know you are lonely, sad, and upset.” The children in his work, however, are clearly cognizant of their discomfort. They stand at attention, glaring up in accusation at the audience placed in the position of the adults that control their world. From this vantage point, the audience takes on the role of the oppressive society that Nara, from the eyes of the children, rebels against.

This underlying rebellious nature comes from Nara’s juxtaposition of the thematic inspiration from children’s books with the altogether contrary stylistic influence of Punk rock. Nara discovered an innate affinity for the dissonant melodies and brash, unrefined nature of the Punk rock movement, and empathized with lyrics saturated with themes of seclusion and angst. The criticisms that the Punk rock artists made concerning society and culture resonated with Nara, already acutely attuned to the inherent isolation he felt around him. Nara displays this discord with society and culture through his artwork, focusing on isolated figures against blank, featureless backgrounds. His figures seethe with an underlying fury characteristic of the ire and rage which play an intrinsic role in the Punk rock persona.

In keeping with this thematic ideology of rebellious accusation, Chinese Girl on the Dish (Lot 509) exemplifies Nara’s emphasis on isolation. A solitary figure standing proudly in defiance against the expanse of green which surrounds her, she seems to hang precariously in the void, secured only by the small white disk on which she has resolutely planted her tiny, black boots. Her scarlet military-style uniform further differentiates her from the contrasting green, positioning the girl in complete divergence from her surroundings. Hands clenched by her side, she stands vigilantly and stiffly at attention. She gazes steadily and solemnly upward, alert and wary of her isolated position. Her tightly pursed lips betray the tension smoldering beneath her penetrating glare. As the audience looks down on her from the high vantage point of an adult, she scowls out from beneath an expanse of black hair, tied up in symmetrical side buns, as tightly wound as the girl herself. Her entire being radiates the rebellious indignant ideals of Nara’s Punk rock influence, though sweetly and simply painted with thick, defining lines consistent with the artist’s picture-book style.

Nara further explores his juxtaposition of the soft appeal of child-like imagery with more sinister undertones of rebellion and dissonance in his sculptural series. In Puff Marshie Mini (Lot 510), the over-sized, bulging eyes, petite facial features, and gently contoured cranium all remain consistent with Nara’s emblematic depictions of wide-eyed children. Puff Marshie Mini exhibits all the qualities which its name evokes. Lacking in sharp angular lines, each plane of the sculpture appears gently inflated, from the softly swollen cheeks and brow to the ropes of thickly defined locks of hair which curve around the face like a defensive cushion, shielding the subtly smiling child in a cocoon of plush protection. The rigidity of the fiberglass medium, however, creates a stark contrast to this deceptively yielding appearance, undermining the softness of form with a severity of substance. Further reflection upon the sculpture inspires greater unease, as the blank, featureless eyes stare unblinking and gaping over a smile with malicious intent harbored in its subtle curves. While not as overt in rebellious intent, Puff Marshie Mini still continues Nara’s subversive examination of suppressed conflict.

Nara’s work constantly balances the conflicting influences which he utilizes to expose the discord inherent in the frequent isolation of an individual within a society seemingly rife with networks and connection. Just as tension teems behind the exterior innocence of his figures, insinuation and intention saturate his deceptively simple paintings and sculpture. As the artist himself states, “I work very hard to make sure my art does not produce a superficial image, that there is much more depth to it.” It is this depth and implication that draws such a diverse and ardent following across the globe.

Modern and Contemporary Art Evening Sale

Ravenel Autumn Auction 2012 Hong Kong

Sunday, November 25, 2012, 7:30pm